Le Bitcoin est-il licite dans l’Islam ?

15 min de lecture

- Bitcoin

Savoir si le Bitcoin est halal (licite) ou haram (illicite) en vertu du droit islamique, la Charia, continue à susciter des débats parmi les érudits et les communautés musulmanes. Les principes de la Charia qui soulignent et imposent une finance éthique, une transparence et d’éviter le riba (intérêt), le gharar (incertitude excessive) et le maysir (jeux de hasard), ont tendance à focaliser la discussion sur la licéité du Bitcoin de par sa nature en tant que monnaie ou devise décentralisée (ou non) qui est à la fois numérique et intangible, et dont la valeur fluctue de manière importante. Ceci a engendré de nombreux avis juridiques sur la question.

Certains érudits, comme le Sheikh Abdullah bin Sulaiman al-Manea, soutiennent qu’il est halal en le comparant à l’or en raison de sa rareté et de son utilité en tant que réserve de valeur et moyen d’échange sans intérêts. D’autres, comme Mufti Taqi Usmani, le considère comme haram en soulignant sa volatilité, sa spéculation et son manque de valeur intrinsèque ou soutenue par une autorité centrale, le comparant aux jeux de hasard.

Alors que les Musulmans constituent un quart de la population mondiale, ce débat est important pour la capacité du Bitcoin à continuer son adoption au niveau international. Pour arriver à une base juridique solide sur la question, le caractère innovant et la structure unique du Bitcoin doivent être analysés en prenant compte de l’éthique financière traditionnelle islamique, une tâche extrêmement ardue ayant donné lieu jusqu’à présent à une variété d’interprétations alors que les érudits évaluent ses implications pratiques et théologiques dans le contexte des anciennes écritures.

Chez CoinShares, nous avons été témoins de l’intérêt accru de nos clients pour cette question, tant au Moyen-Orient que dans le secteur bancaire privé européen offrant des services à des clients du Moyen-Orient. Avec l’allocation récente d’ETF Bitcoin par Mubadala, le fonds souverain des EAU (440 millions de dollars), nous pensons qu’il est grand temps d’écrire sur le sujet, de recueillir et de discuter des conclusions disponibles sur la question dans un seul article.

Trois sources sont utilisées pour comprendre les règles, les définitions et les terminologies dans la Charia

Mufti Muhammad Abu-Bakar explique que la Charia repose sur trois branches principales de connaissances et de compréhension lors de la création de fatwas pour la Charia. La première est une révélation directe d’Allah codifiée dans le texte coranique ou le hadith (enregistrements du comportement exemplaire du dernier prophète Mohammed). La seconde source est la langue arabe, sa sémantique et les limites de ses définitions. La troisième source est l’urf qui signifie une pratique coutumière au sein de l’ummah, la communauté musulmane.

Ces branches ne sont pas égales et les connaissances de la révélation l’emporteront évidemment sur la langue ou la coutume. Ensemble, ces trois sources et les interprétations juridiques basées sur celles-ci et recueillies au cours de plusieurs centaines d’années, ont créé un grand nombre de précédents juridiques islamiques qui sont assez similaires à la façon dont la Common Law est pratiquée dans l’occident.

En finance islamique, toute chose est considérée à l’origine comme étant licite

Pour fournir aux lecteurs qui, nous présumons, ne seront peut-être que vaguement familiers avec ce sujet, un fondement de la Charia aussi solide que nous pensons pouvoir fournir, nous commençons par les principes philosophiques du droit financier islamique.

La jurisprudence financière islamique ou fiqh al-muamalat régit les transactions économiques en vertu de la Charia dans le but de garantir la justice, l’équité et un comportement éthique. En finance islamique, en tant que principe général du fiqh, tout est considéré comme licite (mubah) par défaut à moins qu’il n’y ait une preuve explicite dans le Coran, l’Hadith ou un avis unanime des ulémas (ijma) qui l’interdit. Ce concept connu sous le nom d’al-asl fi al-ashya’ al-ibaha (« toute chose est considérée à l’origine comme étant licite ») s’applique aux transactions matérielles (muamalat) comme le commerce, les contrats et les opérations financières, pourvu qu’elles ne violent pas la Charia.

En d’autres mots, le fardeau de la preuve incombe au défenseur de l’illicéité. De plus, une cohérence logique est strictement nécessaire et les preuves de l’illicéité ne peuvent pas être logiquement incohérentes en ce qui concerne les autres preuves du contraire. Selon la fatwa sur le Bitcoin (et le bitcoin) de Mu’aawiyah Tucker :

« Contredire ce principe sans preuve valable et importante est une question plus sérieuse que d’adhérer au principe tout en ignorant les aspects corrects de l’illicéité. »

Donc par exemple, un nouvel outil financier comme le Bitcoin et une nouvelle monnaie comme le Bitcoin sont tout d’abord licites sauf preuve stricte d’un conflit avec les règles de la Charia.

Les principes fondamentaux de l’illicéité incluent l’usure, l’incertitude excessive, les jeux de hasard et le manque de partage des risques et des profits

Certains des principes clés illicites de la Charia comprennent l’interdiction du riba (littéralement l’excès, mais généralement interprété comme l’usure ou l’intérêt) qui proscrit les gains abusifs provenant de prêts et du gharar (incertitude excessive) qui prohibe les contrats avec des conditions ambiguës ou des risques excessifs. Le Maysir (jeux de hasard) est également interdit, rejetant les opérations spéculatives sans but productif. Les transactions doivent être adossées à des actifs, liées à une valeur tangible comme des biens ou des services et promouvoir le partage des risques entre les parties, comme dans les modèles de mudarabah (partage des profits) et de musharakah (partenariat).

La circulation des richesses est encouragée avec le zakat (aumône obligatoire) alors que l’accumulation est découragée. Ces règles dérivées du Coran, de l’Hadith et du développement de consensus actifs et continus des érudits afin d’aligner la finance aux objectifs moraux en favorisant un système qui donne priorité à l’aide sociale et interdit l’exploitation.

Les désaccords sur la licéité se résument souvent à des interprétations différentes de questions et définitions clés

En tant que non érudit, nous souhaitons être extrêmement prudents avec la présentation de nos conclusions à ce sujet. Nous sommes parfaitement conscients de nos connaissances de base limitées sur le sujet. Nous demandons donc la clémence des experts en échange de l’humilité de notre présentation.

Nous souhaitons également être parfaitement clairs que ce dont nous parlons dans cet article est uniquement la licéité des achats, ventes et transactions de Bitcoin au comptant et non des dérivés de toute sorte, car ceux-ci nécessitent une analyse séparée.

Sans aller trop en détail du fiqh al-muamalat, d’après ce que nous avons pu comprendre, il s’agit d’une série de questions et de définitions clés dont diverses interprétations juridiques ont tendance à dépendre :

Si le Bitcoin est māl (un actif, un patrimoine et secondairement, s’il est tangible ou intangible)

Si le Bitcoin est une devise/monnaie et secondairement, si le Bitcoin a une valeur intrinsèque

Si le Bitcoin est excessivement incertain ou plus proche des jeux de hasard

Si le Bitcoin facilite un comportement immoral comme la criminalité

En bref, si le Bitcoin s’avère clairement correspondre au point 3 ou 4, il serait haram. En revanche, s’il correspond aux définitions de māl ou devise/monnaie, ce serait un solide argument qui prouve qu’il n’est pas correctement démontré que le Bitcoin est haram et qu’il est alors par défaut halal.

Les désaccords peuvent être résumés dans le tableau suivant soulignant les principales questions avec des exemples d’arguments pour et contre :

Sans prendre position sur aucun de ces points, nous offrons quelques sources et citations pour aider les lecteurs avec leur propre interprétation ou leur propre point de vue sur laquelle des fatwas ils estiment correctes.

1. Dans son rapport de 2018 analysant le Bitcoin du point de vue de la Charia, Mufti Muhammad Abu-Bakar déclare :

« Dans la Charia, l’exigence fondamentale pour une contre-valeur ou contrepartie est qu’elle ait le statut de māl, ce qui signifie bien. »

Il poursuit en expliquant que les deux caractéristiques déterminantes de māl sont si quelque chose est désirable et si cette chose peut être transférée d’une personne à l’autre. En d’autres mots, toutes les choses qui peuvent être possédées et ont de la valeur.

Si l’argument est que la propriété intellectuelle est tangible, car elle est « écrite », alors le contre-argument est que le Bitcoin est également écrit. À ce titre, un Bitcoin est aussi tangible que toute chose qui est écrite numériquement comme les entrées électroniques dans la mémoire d’un ordinateur. Ce point de vue est soutenu par Shaykh Taqi Usmani qui dit que dès que des choses non tangibles comme des droits et des avantages acquièrent de la valeur selon la coutume, elles deviennent māl.

2. En ce qui concerne la question sur la monnaie, Mufti Faraz Adam déclare :

« Le trait caractéristique de la monnaie dans l’Islam est qu’elle n’est rien d’autre qu’un moyen d’échange. Elle n’est que ça et ne sert à rien d’autre que ça. Ce n’est pas un bien à échanger ou à louer. Ce n’est pas un actif comme les autres actifs, ni un service comme les autres services. »

Dans cette définition, il s’appuie sur les anciennes écritures de l’imam Ibn al-Qayyim et de l’imam al-Ghazali qui déclarent que l’argent n’est pas quelque chose à rechercher en soi, mais un moyen d’acquérir tous les autres actifs. Al-Ghazali dit que :

« Il est précieux en lui-même, mais non désiré pour lui-même. »

D’après ce qui précède, nous pouvons voir combien certains érudits insistent sur le fait que la monnaie doit avoir de la valeur elle-même, une valeur intrinsèque. Le problème est que la valeur intrinsèque n’est pas bien définie. Nous avons beaucoup abordé cette question par le passé et au moins en ce qui me concerne, la valeur intrinsèque ne me semble pas être un concept raisonnable. Je pense que la valeur est entièrement subjective.

Dans tous les cas, la valeur intrinsèque ne devrait pas reposer sur le fait de savoir si une chose est tangible. De nombreux éléments intangibles ont évidemment de la valeur comme la propriété intellectuelle. Nous faisons ici référence à la discussion ci-dessus sur les actifs qui peuvent être intangibles.

Si quelque chose qui est une monnaie ou une devise du point de vue de la finance islamique repose principalement sur le fait qu’elle est utilisée comme moyen d’échange, ce que l’on peut considérer comme sa fonction définitionnelle par excellence, mais certains érudits font également valoir qu’elle doit être utilisée comme réserve de valeur et unité de compte. Dans le premier et deuxième sens, le Bitcoin est clairement une monnaie, car de nombreuses personnes l’utilisent pour échanger d’autres biens et services, ainsi que comme réserve de valeur. De moins en moins de personnes utilisent le Bitcoin pour fixer le prix de choses, mais le nombre de produits libellés en Bitcoin, bien que très peu, n’est certainement pas zéro.

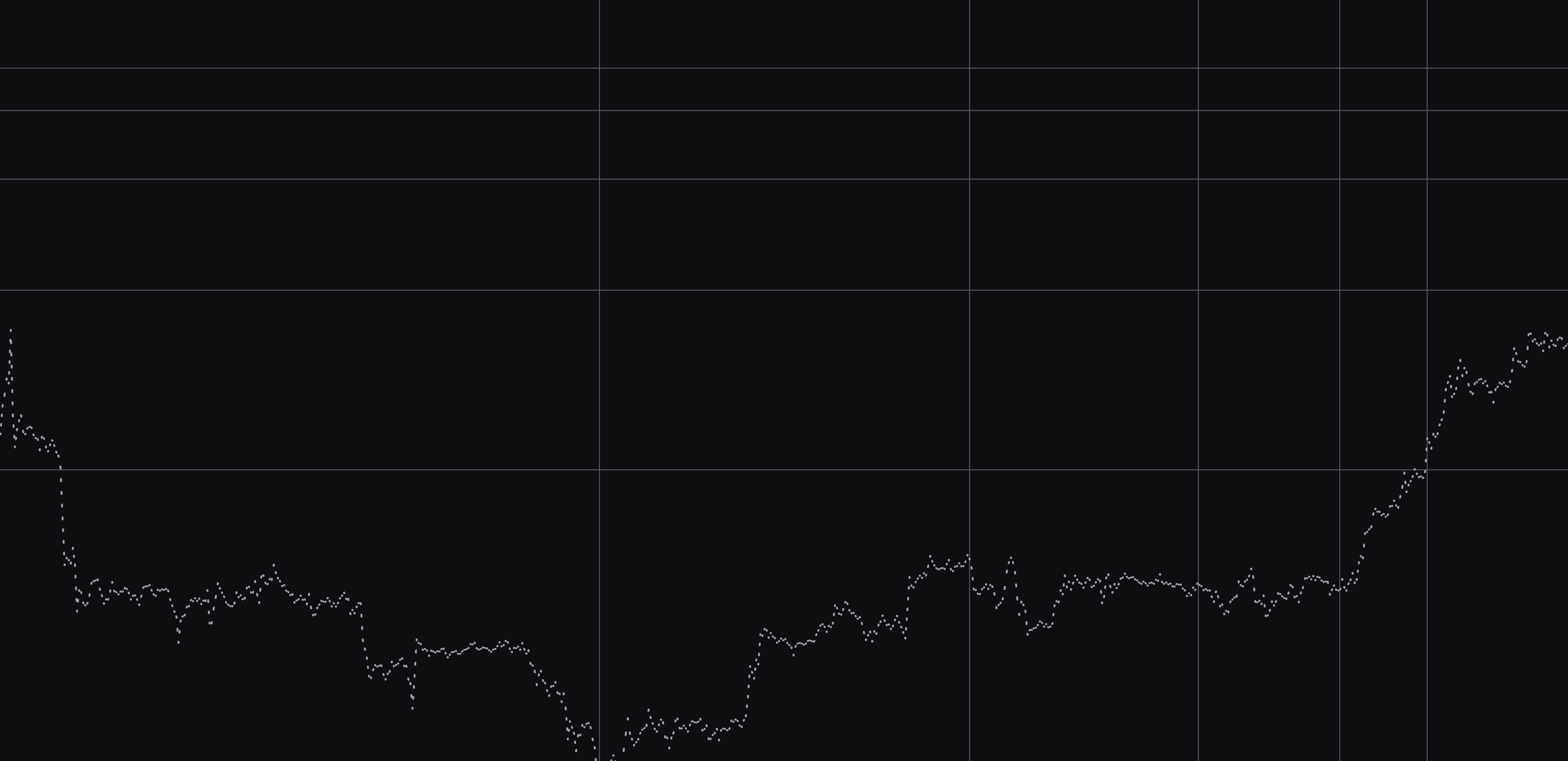

3. Ensuite, nous examinons ce qui a été dit concernant le Bitcoin comme étant excessivement incertain. De nombreuses fatwas déclarant le Bitcoin illicite se basent considérablement sur cette interprétation. Nous n’avons pas besoin de démontrer que la valeur du Bitcoin fluctue, parfois rapidement, ceci étant de notoriété publique. Apparemment dans ce cas, que l’incertitude soit excessive est un peu subjectif, car nous sommes témoins d’un désaccord général à ce sujet.

Le point le plus fort à ce sujet est apparemment que la volatilité du prix d’un objet est externe à l’objet lui-même, il est donc difficile de soutenir que quelque chose est intrinsèquement volatile à moins qu’elle soit explicitement conçue de telle sorte et le Bitcoin n’est pas conçu pour être excessivement volatile. Et puisque le prix de toutes les choses est au final le résultat de l’offre et de la demande, le fait de savoir si quelque chose est excessivement volatile par rapport à d’autres choses doit en fin de compte être déterminé à l’aide de l’urf ou la coutume. La volatilité du Bitcoin est actuellement du même ordre que les plus grandes actions au monde, dont aucune n’est considérée comme étant haram. Le pointer du doigt pour sa volatilité excessive semble donc incohérent. Dans le même esprit, nous ne pouvons systématiquement revendiquer que le Bitcoin est semblable aux jeux de hasard de par sa volatilité sans également faire valoir que négocier de l’or, de l’argent ou des actions comme Tesla or Nvidia est également semblable à des jeux de hasard.

4. Enfin, nous arrivons au point de savoir si le Bitcoin facilite la criminalité. Nous nous trouvons également ici dans un domaine d’interprétation très subjectif. Puisque techniquement tout peut être utilisé pour la criminalité, une interprétation selon laquelle le Bitcoin la facilite se résume à l’impression que la personne faisant l’interprétation a de l’utilisation principale du Bitcoin. Plusieurs érudits, dont Shaykh Shawki Allam et Mufti Taqi Usmani, sont de cet avis, ainsi que la Direction des affaires religieuses de la Turquie. Beaucoup s’appuient sur le fait que le Bitcoin n’est pas approuvé par des organismes légitimes comme un moyen d’échange officiel.

Mais de nombreux autres érudits prennent la position qu’il n’y a rien d’inhérent au Bitcoin faisant qu’il facilite la criminalité. Les gens peuvent choisir de l’utiliser pour des activités criminelles, mais le contraire est également vrai. Plusieurs érudits s’entendent également sur l’interprétation selon laquelle la monnaie est principalement une question de convention et ne nécessite donc pas le soutien des autorités pour être utilisée comme moyen d’échange. À nouveau, ceci laisse une grande liberté d’interprétation. Personne ne peut contester que beaucoup de gens, même des millions, utilisent le Bitcoin comme moyen d’échange. Le fait que cela compte comme une « utilisation généralisée » dans un monde où vivent 8 milliards d’individus est cependant une question d’interprétation.

Les interprétations tendent à une plus grande acceptatione

Alors qu’il y a toujours des désaccords sur la question au sein de la communauté des érudits musulmans, la tendance est pour une plus grande acceptation. Beaucoup des principales fatwas à l’encontre de la licéité du Bitcoin ont à présent plus de 5-7 ans et ont été émises à une période pendant laquelle les connaissances générales sur le fonctionnement du Bitcoin étaient moins avancées qu’à présent.

Il nous semble que cela est juste une question de temps avant que la communauté n’arrive à un consensus et si la tendance actuelle continue, nous pensons qu’il est probable que le consensus finisse par le reconnaître comme licite. Nous trouvons que les décisions les plus récentes sont de plus en plus impressionnantes quant aux connaissances du protocole et du réseau, et l’utilisation croissante du Bitcoin ainsi que sa notoriété publique affaiblissent l’argument selon lequel il est principalement utilisé pour un comportement immoral.

Jusqu’à ce qu’un consensus soit cependant atteint, nous encourageons les lecteurs intéressés à consulter les différentes décisions en détail et à se faire leur propre opinion selon leurs propres croyances et compréhension. Nous joignons une multitude de sources et de métasources ci-dessous et invitons les lecteurs possédant davantage de connaissances sur le sujet que nous à nous faire part de leurs commentaires et éclaircissements.